Children and their families

The first pupils

Sir John Cass was quite clear about who he wanted to help by starting his school.

When it was opened a newspaper report said it was:

“for the poor children of the ward of Portsoken, to be educated in the knowledge of the Christian religion according to the principles of the Church of England”.

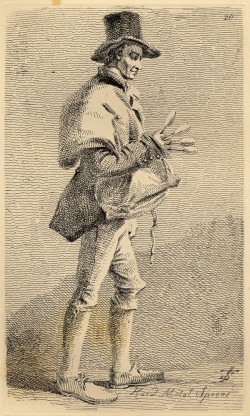

At this time education was not a right. No one kept exact records, but it is likely that only around half of all London children got to go to school at all. And thousands of young children went out to work, often at dirty and dangerous jobs. One of the most dangerous was climbing chimneys to sweep them, but many other under 10s worked long hours for little pay at jobs with no future prospects.

There were fee-paying schools for the better-off, and there were also some, but not enough, places in charity schools set up to give poorer children a chance in life.

We know that to begin with Cass planned that his school should be much smaller, accepting only 20 pupils, boys only, and should offer scholarships to the leavers to go to university or to be trained for a trade.

But as time went on he changed his mind, and decided to offer places to 50 boys and 40 girls. As an employer, Cass knew that young people with skills in reading, writing and arithmetic would be much more likely to obtain work or training, and he directed that the education in his school should be planned with a view to supporting the pupils’ likely futures. Realistically, most of them were likely to be apprenticed to a trade or go into service .

When the school re-opened in 1749 the trustees advertised for families to attend for interview with their children. All the applicants had to be been born in the ward of Portsoken and to be members of the Church of England.

Children admitted on 21st June 1749

John Fulslow Isabella Langdon

Michael Berrisford Colsman Elizabeth Cooper

Robert Williams Mary Tulston

Henry Shallot Elizabeth Banbery

John Burroughs Hannah Hope

Hammond Tornhills Ann Wilson

David Waterlow Elizabeth Aston

Williams Darquitt Sarah Geeny

Charles Linton Isabella Edwards

Charles Moreland Hester Trinder

Joseph Tux Mary Bridgwater

John Geeny Ann Dunkley

Rosemas (sic) Whitehead Ann Bishop

David Richards Susannah Linton

Joseph Thomas Chesney Elizabeth Goldsmith

James Smith Sarah Warner

Philip Woodman Lovell Eleanor Burroughs

Roger Thorseby

Joseph Williams

John Pearce

Humphrey Newell

Thomas Newell

Samuel Rand

George Bird

George Gray

And a week later

Robert Lepper Elizabeth Geary

George Budelow Sarah Hartley

Samuel Daniels Elizabeth Chevalier

Robert Buswelly Rebecca Richards

John Pounceby Ann Ridley

Thomas Baytes Elisabeth Valentine

Charles Lowder Mary Blackridge

William Chalton Sarah Webb

John Crawford Sarah Sharp

William Pearpoint(dismissed) Mary Bullen

Charles East Esther Badman

Robert Barnesbury

Richard Miller

William Wharam

William Cooper

These children were admitted by interview – we do not have their addresses or details of their parents. Neither are exact ages recorded, but it is likely most were seven or eight years old.

The trustees decided that, for future vacancies, they would take it in turns to “present” a suitable child. And for several years after this, information is given about each new child who gained a place in the school – usually the minute book records the name of the child and of his or her parents, their address, father’s occupation and the child’s date of birth are all usually listed.

We know, too, that these were not the very poorest local children, or those who had been left without friends or relatives to care for them. For in 1735, because “churchgoers were greatly obstructed and annoyed in going out of the church after sermon on Sunday by the passageways being crowded with beggars”, a work house was opened in Houndsditch. And it was here that the helpless went for shelter. We know that conditions in the workhouse were comparatively humane – for example, the house was decorated at Christmas and the residents given a special dinner with extra meat, milk and puddings. But still one resident in five died each year.

Of the children who were sponsored by a trustee to be given a place in the school in the early 1750s, almost half had lost one parent. All the fathers mentioned had a job of some sort, and most had a skill. There were, for example, carpenters, blacksmiths, butchers, gunmakers, tailors, a wine cooper and a cabinet maker. It is likely that at least some of these families were earning a fairly good living, but it is clear also that most of the trustees were keen to help where there was most need.

All the addresses are very close to the school – the majority in “courts” off the Minories or Houndsditch. (link to places page), and some in premises over shops. It was still very usual for craftspeople and shopkeepers to live and work in the same premises. Often there would be a shop in a front downstairs room, a work room at the back and living space upstairs. For the less well off, home for a whole family might be just one room. By the middle of the eighteenth century many rich and fashionable people had moved out of the City to live in the West End, leaving many grand houses to be sub-divided. Often they became blocks of overcrowded bed-sits.

And if some of the school’s pupils came from quite prosperous families, others were certainly from poor and sometimes chaotic backgrounds. For example, in 1752 Roger Theresby was in trouble. He had not attended school for six weeks; his father had said he was ill, but it turned out that the father had pawned the buttons from his son’s school suit, and so the child could not attend.

In that instance, the trustees took the boy back. But there were constant problems with children being sent to school dirty and unkempt, or kept away for long periods. In most cases the parents were summoned to appear before the trustees and warned, and if improvements were not made, the child was excluded.

Over a period of several months in 1751, Mary Foulsham’s father was repeatedly warned for sending his daughter to school in a “very dirty and battered condition” – sadly, the final result of this was that the little girl lost her chance of an education.

It was quite common for a child to die. When this happened it was usual for the bereaved parent to attend a trustees’ meeting to report the death and to return the child’s uniform. Often the trustees would appoint another child, sometimes on the spot to fill the vacancy, and would pass on the returned uniform to the new girl or boy. When Mary Pinks died in 1751, her uniform was passed on to Mary Johnson.

All the children’s school career was quite short – from seven to thirteen or fourteen. It was expected that all pupils would have training or a job to go to, and in some cases a girl or boy was kept on for a few extra months, but sometimes that trustees would give notice they would have to leave on a stated date whether they had anywhere to go or not.