The Royal African Company

The Company was set up in the 1660s to help British business men to invest profitably in Africa. James, Duke of York (later James II) was involved, as were many aristocrats as well as City investors. In the early days of the company, gold and ivory as well as slaves were some of the most profitable areas of trade.

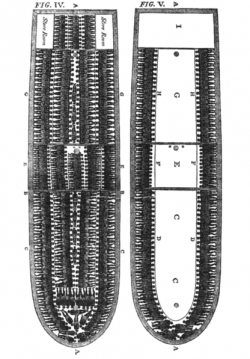

But by the 1690s the company traded mostly in slaves, and most of its investors’ money was used to hire slave ships that visited West Africa, collecting slaves who had been bought by permanent representatives of the company from local rulers, and going on to the West Indies and Virginia to sell their human cargo, whose labour was needed in the sugar and tobacco trades. At this time around 5,000 slaves a year were being traded. But in 1698.Parliament agreed to break the Company’s monopoly, largely because it could not keep up with the demand from the sugar and tobacco planters. The Company was, however, to remain part of the slave trade until the 1730s.

But by the 1690s the company traded mostly in slaves, and most of its investors’ money was used to hire slave ships that visited West Africa, collecting slaves who had been bought by permanent representatives of the company from local rulers, and going on to the West Indies and Virginia to sell their human cargo, whose labour was needed in the sugar and tobacco trades. At this time around 5,000 slaves a year were being traded. But in 1698.Parliament agreed to break the Company’s monopoly, largely because it could not keep up with the demand from the sugar and tobacco planters. The Company was, however, to remain part of the slave trade until the 1730s.

For several years Cass served in various roles on the Company’s committees, including for a time on the executive committee which met regularly to set budgets and give detailed instructions to the captains of the slave ships. The instructions included details of everything from the prices to be paid and asked to the amount of food given to crew and slaves to the records to be kept of how many of each died. Each ship carried a chaplain, and every day began with prayers. Cass and all his colleagues signed each letter individually, and received regular reports from the ships’ captains and the company’s representatives at the permanent trading posts they had set up in West Africa.

The trade was well established by the time John Cass was involved in it – he was not among those who invented it and he was far from being alone or even unusual in what he did. He was, however, among those who were fully aware of the human cost of obtaining his and his colleagues’ profits. In counting that cost, it must also be remembered that the death rate among the ships’ crews was sometimes even higher than among the slaves. The lives of so-called free Britons were just as expendable as those of enslaved Africans.

The trade was well established by the time John Cass was involved in it – he was not among those who invented it and he was far from being alone or even unusual in what he did. He was, however, among those who were fully aware of the human cost of obtaining his and his colleagues’ profits. In counting that cost, it must also be remembered that the death rate among the ships’ crews was sometimes even higher than among the slaves. The lives of so-called free Britons were just as expendable as those of enslaved Africans.

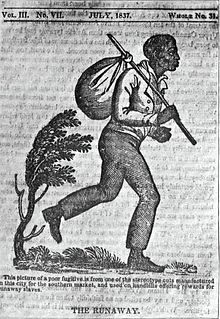

At this time slavery on British soil was controversial and possibly illegal, and there were a number of cases when judges ruled in favour of run-away slaves who applied to them on the grounds that no one in this country would be the property of another human being. However, also at that time it was the British abroad who were the world’s busiest slave traders, although closely rivalled by the Dutch and Portuguese. Certainly Cass and his colleagues made very substantial sums of money from their Africa Bonds (shares in the company), especially after the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht gave Britain a very useful edge in the running of the Atlantic slave trade.