Livery Companies

For hundreds of years, anyone who wanted to set up a business or get a job in London needed to belong to a livery company. Each trade or occupation, from archers to wheelwrights, had its own closed group, and no one who was not a member could either work in that occupation or be trained in it.

Most of the companies had their own halls, which operated as meeting places, courts and dining clubs. And, as they are today, the Aldermen and Lord Mayor of London were elected from among their members. There was an Alderman elected for each ward of the City, and the Lord Mayor was elected each year from among the 25 Aldermen. As the Lord Mayor and Aldermen controlled the whole administration of the City, these were very powerful men. So anyone who wanted to get on in business or politics had to belong to a livery company, preferably one of the richer, grander ones, and to serve on its various committees so as to become eligible for the top jobs.

Most of the companies had their own halls, which operated as meeting places, courts and dining clubs. And, as they are today, the Aldermen and Lord Mayor of London were elected from among their members. There was an Alderman elected for each ward of the City, and the Lord Mayor was elected each year from among the 25 Aldermen. As the Lord Mayor and Aldermen controlled the whole administration of the City, these were very powerful men. So anyone who wanted to get on in business or politics had to belong to a livery company, preferably one of the richer, grander ones, and to serve on its various committees so as to become eligible for the top jobs.

In addition, the livery companies controlled training for most occupations. If, for example, a boy wanted to become a baker, he had to become apprenticed to a master baker. This meant the apprentice was trained in return for a fee, usually for seven years, after which he had to pass an examination. After that he had to work for as a journeyman under supervision before he was allowed to work independently. In earlier times some occupations were open to women as well as men. By Cass’s time this was becoming rarer, but there were still some independent women, and it was common for a woman to take over her husband’s business.

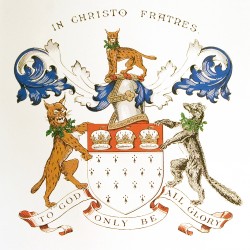

In the early days of livery companies, usually the members of a particular company worked in the trade named. For example, a Master Goldsmith was usually an expert maker of gold and silver objects. But by Cass’s time the Goldsmiths’ Company included bankers and women mantua makers as well as metal workers on its books. This was true, too, of the Skinners’ Company. Formerly most of its members had been connected with the fur trade – now for the most part they were general traders, merchant venturers, many of them with international business interests. It was one of the richest and most influential of the companies.

In the early days of livery companies, usually the members of a particular company worked in the trade named. For example, a Master Goldsmith was usually an expert maker of gold and silver objects. But by Cass’s time the Goldsmiths’ Company included bankers and women mantua makers as well as metal workers on its books. This was true, too, of the Skinners’ Company. Formerly most of its members had been connected with the fur trade – now for the most part they were general traders, merchant venturers, many of them with international business interests. It was one of the richest and most influential of the companies.

So, with the agreement of the Carpenters’ Company, Sir John Cass became a Skinner. He was allowed to miss out several of the usual stages of promotion, and became Master of the company within two years. The move to a more prestigious company was partly to help his bid to become Lord Mayor.