1918

It’s 1918. Londoners, like the inhabitants of most of the world’s cities, are getting used to the idea that the Great War is over. No one knows exactly how many people had been killed in the four years since 1914 – perhaps three million, perhaps five.

War came to London for the first time in three centuries. And for the first time ever, the city was attacked from the air. Terrified Londoners sheltered in churches, cellars and underground stations. One summer day in Poplar, sixteen children died when a bomb fell on their school, and sixteen adults when a train in Liverpool Street station suffered a direct hit.

Many families sent their children to the country for safety. Sir John Cass’s School stayed open, but with fewer children. Many former pupils and some current teachers went off to fight. The school managers took little official notice of the war, pausing only to deplore the shortage of sugar and butter.

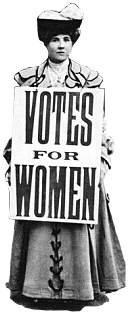

Now it’s over, and life for the survivors has changed forever. Women, after years of struggle, have finally won the vote, a victory brought about partly because so many worked during the war Most of them will not give up their independence now. So the girls of the Cass school now have many more choices open to them.

Now it’s over, and life for the survivors has changed forever. Women, after years of struggle, have finally won the vote, a victory brought about partly because so many worked during the war Most of them will not give up their independence now. So the girls of the Cass school now have many more choices open to them.

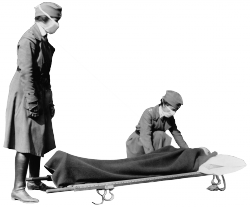

But as London recovers and begins to plan for the future, a fresh disaster has struck. The authorities refused to take Spanish Flu seriously at first. But it can kill in hours, preferring the young and the healthy. It will claim five times more victims than did the war. Londoners walk about with their faces wrapped in scarves to avoid infection. In playgrounds and gardens, children have a new nursery rhyme.

“I had a little bird

Its name was Enza

I opened the window

And in-flu-enza”

At the Cass school, the headmaster is organising a collection for a memorial to the Old Cassians who died in the war. Nobody will keep a count of the ones who die of the flu.